The AI Arms Race: Innovation or Overbuild

Written by: Paolo LaPietra, CFP®

Every generation gets its defining investment story, and right now it is AI. Not the harmless “let’s ask ChatGPT” version, but the trillion-dollar, power guzzling, data center everywhere version that is reshaping the market. The numbers have reached a point where they barely feel real. Nvidia reached a five trillion-dollar valuation last month. Microsoft and Apple sit at four trillion. Google crossed the one hundred-billion-dollar quarterly revenue mark. Meta is increasing spending so aggressively you would think it was preparing to build its own city, and if Meta City ever becomes real, I am calling dibs on the naming rights.

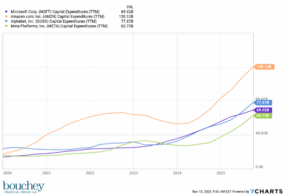

As impressive as all of this sounds, the real story is no longer about software. It is about capital expenditures, and that is where innovation and overbuilding begin to blur together.

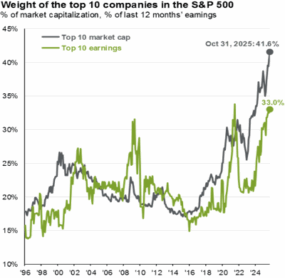

Capital spending tied to AI has exploded. Microsoft, Amazon, Google and Meta are projected to commit roughly three hundred to four hundred billion dollars to data centers, chips, networking equipment and energy infrastructure this year. Entire financing ecosystems are forming around these commitments. OpenAI plans to spend well over five hundred billion dollars in the coming years, supported by circular arrangements with Oracle, Microsoft, Nvidia, AMD and AWS. AI related corporate debt issuance continues to climb. Since late 2022, AI linked names have contributed most of the returns, earnings growth and capital spending expansion within the S&P 500. This is not a modest investment cycle. It is an arms race.

The uncomfortable part is that on the revenue side we are still very early. OpenAI generates around twenty billion dollars in annual revenue. Meta and Alphabet continue to tell investors that several more years of heavy spending are likely before meaningful monetization appears. Even CoreWeave, which became one of the most celebrated new AI infrastructure companies following its IPO this year, recently explained that delays in data center construction would create a near term revenue hit. In short, the gap between what is being spent and what is being earned is not narrowing. It is widening.

This tension of massive investment upfront and uncertain cash flow at the back end is not new. Investors have seen versions of this movie before. Recent research from Sparkline Capital highlighted the railroad boom of the 1800s and the telecom fiber buildout of the 1990s followed a nearly identical pattern. Both reshaped the economy. Both created decades of real economic value. And both ended with far too much capacity, falling prices and years of poor returns for the companies that spent the most. The NASDAQ telecom index surged in the late 1990s before collapsing by 92% when the excess became obvious. More than twenty years later, it still has not returned to the highs of that period. The technology changed the world, but the earliest investors did not necessarily benefit.

Today’s AI cycle shows some of the same stress points. The Magnificent Seven companies are shifting from asset light, software driven profitability into asset heavy spending patterns that resemble utilities. Their balance sheets are increasingly intertwined as they act as lenders, suppliers and customers to one another. Corporate debt tied to AI infrastructure continues to accelerate, including some of the largest private credit deals ever completed for single data center projects. Expectations for these companies have also become flawless, which creates a fragile setup. When perfection is priced in, even good results can cause sharp selloffs.

So are we witnessing a genuine technological breakthrough or a historic overbuild. The honest answer is both. AI is real. It will reshape industries and improve productivity. But that does not mean the companies spending hundreds of billions on infrastructure today will be the ones who ultimately capture the value. Historically, the biggest winners of major technological revolutions have often been the adopters rather than the builders. Netflix did not lay fiber. Facebook did not construct telecom networks. They built empires on infrastructure that others had overspent on.

For investors, the goal is not to avoid AI, and it is not to chase the companies spending the most either. The goal is to participate in AI’s long-term growth without relying on the perfect execution of a narrow group of mega cap stocks. Diversification matters even more in this environment. Companies that quietly use AI to improve margins, efficiency and productivity may ultimately deliver steadier and more durable returns than the firms trying to win the capital spending race.